FUV Essentials: Chuck Singleton on Patti Smith

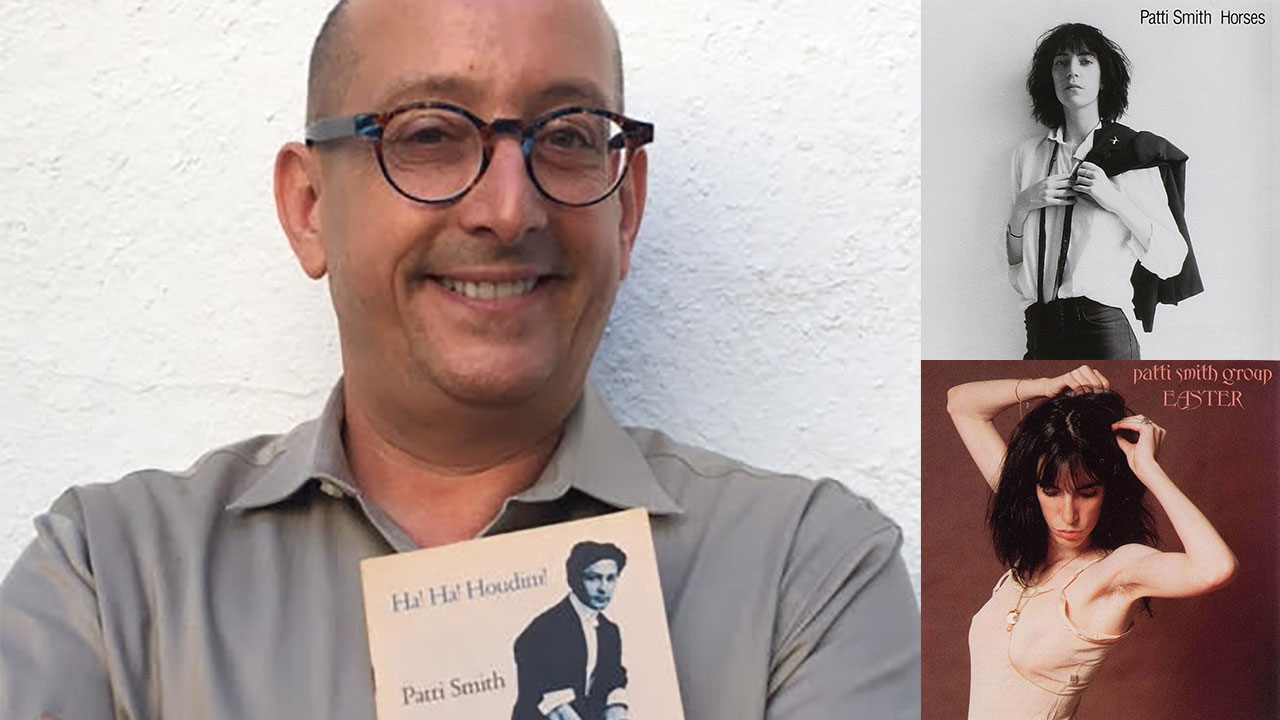

The author with a Patti Smith chapbook, a 1977 Gotham Book Mart purchase (photo courtesy of Chuck Singleton, collage by Laura Fedele)

Patti Smith saved my life.

No, not “literally.” But she was a cultural and social life preserver thrown to me, a child of the mid-Seventies, who was growing up in that other Jersey: South Jersey.

As I learned years later reading her gorgeous memoir, Just Kids, Patti and I share South Jersey roots. It's a region with its own, unique variety of strangeness, and in parts, it's much like the rural South. My South Jersey was the grand, decrepit, and pre-casino Atlantic City. For Patti, it was the Camden suburbs, one of her childhood homes.

Down in Vineland

There’s a club house.

"Ain’t it strange," indeed. As young people, we shared the area’s isolation, and the search for a way out of the limitations of our blue collar communities. For me, much like for Patti, poetry, music, and art were the ticket. As a teen with a head full of the Beats and drawn to New York’s downtown art scene, I would often take the NJ Transit bus to the Port Authority. My stops would include the Gotham Book Mart, Brentano’s, Eighth Street Bookshop, Printed Matter in Tribeca, and other long-departed landmarks of New York book culture.

I was a little late to that scene (Patti had been a sales clerk at Brentano’s in the Sixties, as she details in Just Kids), but no matter. I picked my way slowly through the stacks, returning to A.C. with armfuls of poetry. Patti’s work was among them; works of art that would take me beyond my neighborhood’s stifling boundaries. Punk may have started with the Ramones, but Patti was my gateway drug.

But our first encounter wasn’t music. It came when a college art professor screened an obscure (and for its day, transgressive) little movie featuring her lover and soul mate, Robert Mapplethorpe. The images brought to light a subculture unknown to most 19 year olds. And who was that woman, heard but never seen, running a narrative unconnected to what was happening on screen? The answer came when the same teacher played a new single from New York, a cover of "Hey Joe," more poetry than music. And on the B-side, the poet? musician? read a piece about working in a factory. I wasn’t stuck in a sweatshop, but my parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles might recognize their lives in Patti’s graphic description of physically destructive and degrading work. And I recognized my own path out in Patti’s conclusion:

I'm gonna get out of here,

I'm gonna get on that train,

I'm gonna go on that train and go to New York City

I'm gonna be somebody.

Then came the music. There was her 1975 debut, Horses, with its infamous update of Van Morrison's “Gloria.” For a Catholic kid, just hearing the first line was enough to send me to confession. Rock had been a soundtrack for Sixties rebellion, but in the time since had been pretty much neutered. Not anymore.

People say beware

But I don’t care.

The words are just

Rules and regulations to me

Horses was unlike most anything on record, and experiencing Patti and her band playing “Gloria” live, in all its wild abandon, was eye and ear opening. It was also my first time seeing an artist smash a guitar up close—strings popping, shards at my feet, and the ring of feedback in my ears for a day. What to make of this heady collision of rock, anarchy, androgyny, and the French Symbolists? The whole package was pretty compelling, and in equal parts, self-indulgent excess.

But no matter; I loved her work and stuck with Patti over a cluster of albums that closed the Seventies (Horses, Radio Ethiopia, Easter, Waves), and meshed poetry, rock and rebellion.

Outside of society

Is where I want to be.

Later, when I found my way into radio, Patti’s DIY aesthetic was among the sources that inspired and made me want to teach radio’s tools to whoever wanted to learn.

Hey you.

Come here.

Get up.

Ah, this is the era where everybody creates.

Patti’s music has remained my companion over four decades. A perk of working at WFUV has been meeting her during studio visits. The first time, I told her that she saved my life. She blushed, and we talked about our South Jersey roots. The second time, I stopped by Studio A before soundcheck. Patti was prepping as others would study the Bible, a little hardback in hand.

“Let me show you this,” she said, as she shared a beautiful, early edition of William Blake that had been a gift from Allen Ginsberg. Thinking back on that experience reminds me of what attracted me to this essential punk poet as a teen discovering poetry, art and music, and finding this one-of-a-kind artist who became an activist for democracy and justice.

Listening to Patti today bridges my 60-year-old and 19-year-old selves. Speaking for us both, thank you, Patti Smith.